Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to highlight ongoing research suggesting that numerous football cultures existed in Glasgow and the surrounding area prior to what the Scottish Football Museum has termed as the ‘football explosion’ – referring to the rapid rise of Association football in the city in the aftermath of the first official international match under Association rules on St Andrews Day 1872.

In doing so it seeks to question existing historical narratives, such as, for example, the opinion held by the Scottish Football Annual of 1875 that football in Scotland by the mid nineteenth century had ‘almost died out.’

This paper will present evidence implying that a variety of football traditions were imported into Glasgow by migrants and immigrants over the course of the nineteenth century as well as highlighting an existing culture by people native to the area. This research has been drawn from a database developed over a 21-year period which catalogues and maps the origins of football in its many forms across Scotland from the earliest records up to 1873.

Introduction

The staging of the first official international football match under Association rules on 30th November 1872 had a profound influence on the subsequent rapid growth of the game in Glasgow as well as within the surrounding communities of west central Scotland. This seismic expansion in the weeks and months following on from Scotland’s encounter with England at the West of Scotland Cricket Ground in Partick is referred to within the exhibition space of the Scottish Football Museum as the ‘football explosion’. The chapter entitled Glasgow: football capital of the nineteenth century in Professor Tony Collins’ publication, How Football Began, provides a clear insight into the unprecedented scale of expansion over the course of the 1870s and 1880s.

What is less well known is the general story of football activity within Glasgow in the decades leading up to this historic milestone. Several of the early prominent clubs in Glasgow, both Association and Rugby, have published histories which have been valuable and Dr Graham Curry in his book, The Making of Association Football, has a chapter entitled Glasgow; From Whimper to Crescendo which provides a study of the football scene in and around the city from the 1850s through to the 1870s. More recently Andy Mitchell in his popular Scottish Sports History website has written an interesting article on John Burns Connell, a notable early pioneer of football in Glasgow during the 1860s and 1870s.

My own interest in the subject stretches back to my earliest days working at the Scottish Football Museum. One of my first tasks on joining the organisation in 1999 was to study the little-known story (at that time) of the origins of football in Scotland. During the initial period of research two quotes stood out because they appear, on the face of it, to be completely at odds with each other. The first quote is taken from an article in the inaugural Scottish Football Annual, published in October 1875. The second quote, which relates to the 10-year period leading on from the formation of Queen’s Park in 1867, was handwritten by a fellow staff member on a short note.

“This sport was doubtless gradually brought into the general form it possessed in the middle of the present [nineteenth] century. At that time there were many modes prevalent in England, while in Scotland it seems to have almost died out.“

Source: Scottish Football Annual, 1875, P7.

“How could they have gone from no clubs to brilliant clubs in the space of 10 years if they didn’t have a culture of ‘football’ to build upon?“

Source: Research Note, Scottish Football Museum, 1999.

The first quote certainly appears to chime with the viewpoint that there was limited football activity within the city prior to the four-month period over the winter months of 1872 and 1873 which witnessed the international match being staged and the Scottish Football Association and Scottish Cup competition instituted. That, however, provides no explanation for the question posed by my colleague and can be countered by other references which are more contemporary. For example, this observation from 1856, relates to Glasgow Green,

“Cricket, rounders and foot-ball, the sports most popular here, are now practised as extensively as at any former period. On Saturday afternoons, when the mills and public works are stopped, King’s Park presents a most cheerful and animating spectacle, with its numerous groups of youthful operatives, after the toils of the week, all earnestly engaged in these healthful and exciting games.“

Source: MacDonald, H; Rambles round Glasgow, Glasgow, 1856, P26.

This paper aims to highlight that there was indeed a football culture, or more accurately ‘cultures,’ in and around Glasgow. If the first official international match signalled the lighting of the touch paper to create a football explosion, then there had to already be a large powder keg waiting to be ignited. This paper will outline the following points in order to explain the reasons for the post 1872 football explosion in Glasgow,

- From the 1850s through to 1872 thousands of boys and youths were actively engaged in playing football. This activity included the poorest sections of society.

- An eclectic network of organisations, from cricket clubs to the local rifle volunteer corps provided organisational support as the early football clubs began to form.

- The early Association game in Glasgow, as it developed through the influence of Queen’s Park FC, was from the start ostensibly a working-class game.

- The emerging game not only connected with the native working-class population but appealed to migrant and immigrant communities.

- Due to these factors, organised club football initially under the leadership of Queen’s Park was able to expand significantly once the touch paper was lit.

Parameters to the study

The period covered by this paper runs from 1850, aligning with the ‘mid-century’ timeframe quoted in the Scottish Football Annual, and concludes at the end of 1872 with the hosting of the first official international match under Association rules. The paper attempts to analyse the underlying appetite for Association football prior to the international match of 1872 and therefore has an emphasis on the early clubs, including Queen’s Park FC, which played to that code. However, as the starting point for the introduction of Association football to Glasgow only dates to 1867 with the formation of Queen’s Park, general football activity will be studied in some detail including the emerging rugby football game. This is needed to provide a more rounded view of the football cultures emerging in and around the city. Finally, Glasgow by the 1850s was already interconnected with many towns and villages beyond its border. These connections would strengthen throughout the period through the expansion and improvement of the early passenger rail networks. The communities of Partick and Govan, which today are synonymous with the city, were distinctive and separate entities throughout the period but were very much connected. Further to the west of Glasgow, the Renfrewshire town of Paisley, a major centre for textile production, had a passenger line running into the city by 1840. Out to the east, the neighbouring Lanarkshire towns of Airdrie and Coatbridge, major centres for coalmining and iron production, were connected by passenger rail to Glasgow by 1862. The emerging culture of football clubs was not restricted to the city but to a ‘Greater Glasgow’ network incorporating sports organsations, educational institutions and volunteer corps. Finally, as the title suggests, an emphasis will be placed on highlighting migration and immigration, particularly with respect to the emerging Association football culture.

Social experience of Glasgow

An analysis of the football cultures in and around Glasgow needs to be set within the wider social and economic context. In 1750, around the start of the industrial revolution, Glasgow’s population was estimated to be approximately 23,500. By 1801 the figure had increased to 83,769 and by 1851 it had jumped significantly to 329,096. The twenty years following on from the 1851 census would see a continued expansion of the population through a combination of higher birth rates and increasing levels of migration and immigration. For most people living in the city life was precarious; the poorer sections of society lived in overcrowded conditions in slum housing. Despite the increase in births, disease was a major factor in high mortality rates and low levels of life expectancy and the cholera epidemics of 1848 and 1854 devastated the city. The parish-based system of welfare in Scotland, minimal as it was in smaller rural communities, was often overwhelmed in the larger towns and cities. In Glasgow, the biggest city of all in Scotland, there were inevitably high levels of destitution and pauperism, but important work was undertaken, particularly in the field of education, to reach even the poorest sections of society.

The role of working-class education

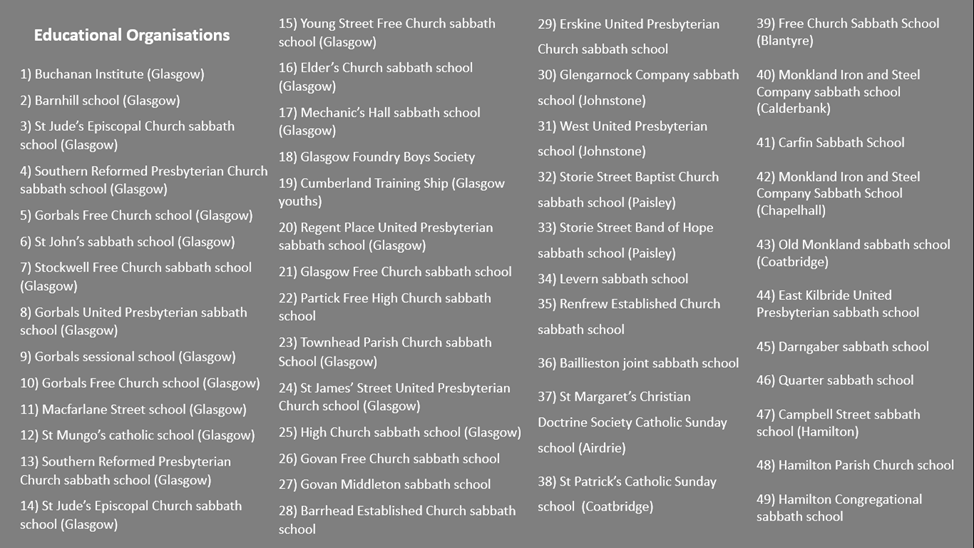

The introductory article in the Scottish Football Annual of 1875, whilst bemoaning the lack of football activity from the mid nineteenth century, also provides some evidence for its existence. The article goes on to say that football “seems to have been confined to the schule green.”1 Glasgow in the years leading up to 1850 was at the forefront of educational reform through visionaries like David Stow, a merchant and educationalist who was responsible for creating Britain’s first teacher training college in 1837. Stow, whose introduction to the education of the poor started off as a teacher in a sabbath school in Glasgow’s impoverished Gallowgate, saw first-hand the impact that poverty and destitution had on the moral corruption of the poor. A passionate advocate for introducing playgrounds at schools, he recognised that organised outdoor activity helped to instil discipline which, in tandem with the classroom, supported the moral wellbeing of children. As early as 1832 he wrote a short article on “Moral and Physical Training” which connected the playground to moral culture.2 His views certainly caught on; by the 1850s a variety of sports and games were being routinely enjoyed by children and youths across Glasgow and the surrounding towns and villages. The outdoor game of football was one of the beneficiaries and is recorded within the activities of sabbath schools, parish schools, industrial schools and religious societies. The slide below provides a list of 49 education-based organisations which have references to football activity within the 22-year period under consideration.

Significantly, sport, including football, is also recorded at refuges. These institutions catered for children drawn from the poorest sections of Glasgow’s society which Stow referred to as the ‘Sunken Class.’ A report on the Glasgow House of Refuge for Boys in 1862 provides an insight into the recreations provided for the boys,

“The directors encourage in and out-door amusements. The playground is daily an exciting scene of youthful sport and recreation. Foot-ball, shinty, bowls, cricket, dragon flying, and other games in their season, are eagerly engaged in. Drill occupies an important place in the boys’ physical training. Their marching and various evolutions would be no discredit to some of our more advanced volunteers…”

Source: Glasgow Courier, 20/02/1862, P2.

Football, as an activity, was enjoyed by all sections of society and the education system helped to ensure that even children from impoverished backgrounds could participate in games. This degree of inclusivity was perhaps best demonstrated in the annual excursions during the summer months which were a notable feature of the school system of the 1850s and 1860s. The numbers involved are certainly significant. Generally, the young people attending such outings were numbered in their hundreds. One gathering of the Glasgow Foundry Boys Society in 1871, had as many as 1,300 in their party.3

Temperance Movement

Healthy outdoor recreation was popularised by the temperance movement as it was viewed as being a useful alternative to the vice of drunkenness. Glasgow was no different to other cities and groups associated with the ‘Teetotal’ movement enthusiastically promoted sport within their portfolio of activities. At the very outset of the period covered there are examples. For instance, in 1850 under the title ‘Temperance and Recreation,’ the Glasgow Chronicle highlights the visit of the Hamilton Total Abstinence Society to the deer parks of the Duke of Hamilton where,

“…the foot-balls and other preparations for amusement were in speedy requisition, and the unbounded hilarity which prevailed unequivocally showed that the most extensive degree of enjoyment is compatible with entire abstinence from strong drink.”

Source: Glasgow Chronicle, 17/07/1850, P6.

The Total Abstinence Association’s links with football were not limited to the Lanarkshire town. Branches at the Gorbals and Bridgeton in Glasgow and Paisley in Renfrewshire also encouraged football games as part of specially planned events.4 Nationally, the Band of Hope movement embraced football as a positive diversion from alcohol and other vices for its young members. Within Glasgow and Lanarkshire, the Band of Hope branches at Hutcheson, Newarthill and Chapelhall are linked to football activity.5 The most productive organisation within the temperance movement, however, was the Glasgow Abstinence Union. This organisation was quite prolific in organising excursions where football was often a popular activity. Newspaper adverts promoted up and coming excursions with, for example, the twelfth excursion of 1863 (to Ferenze Braes in Renfrewshire) proclaiming that “Foot-Balls and Hand-Balls will be provided.”6 The organisation opened a public park in 1862 which was named Gilmorehill Gardens and promoted “Bowls, Quoits, Football, Skittles, Aunt Sally, Volunteer Handicap, Jack’s Alive, Croquet, and a great variety of other games.”7 The promotion of football, however, would be short lived at the park after complaints were received that the game was “interfering with the comfort of visitors.”8

Other football activity

The excursions of the summer months were not just restricted to children and youths. A study of newspapers indicates that work outings were also a popular activity and must have been a source of much anticipation and excitement for iron workers, coal miners and factory workers alike. The range of employers that support football activity during these excursions vary, from a Flour Mill and a Wholesale Stationer in Glasgow to an Iron works in Coatbridge and a colliery in Hamilton.9 One excursion that stands out is the outing of the employees of William McLennan, boot and shoe manufacturer in Glasgow, who, in 1861, enjoyed a trip ‘doon the water,’ travelling by steamer to the picturesque town of Dunoon situated on the Cowal peninsula. At the holiday residence of their employer the party of excursionists enjoyed “…dancing, foot-ball, and various other games…”10 The Ancient Order of Foresters friendly society and the Independent Order of Good Templars also organised outings in different parts of Scotland. In 1869, a “Grand Demonstration” at Elderslie House saw members of the Paisley and Govan courts enjoy an afternoon of “football, racing and jumping” while in 1871 at Chatelherault, near Hamilton, local members of the Cadzow Templars Lodge enjoyed a day out involving “cricket, football and other sports.”11

Finally, football activity was recorded in the network of asylums across Scotland. Montrose Asylum in Angus even had its own football club by 1869.12 In Glasgow and the surrounding locality sport was encouraged as an opportunity to support the wellbeing of the inmates. The report from commissioners in 1867 commented of the Glasgow Royal Asylum that 173 men and 87 women resident in the asylum attended amusements while an additional 10 visited the institution for the same purpose. Cricket and football were listed as popular summer activities.13 Excursions were also undertaken and in 1871, through the undertaking of the Barony Parochial Board in Glasgow, the Barnhill Asylum enjoyed a visit to the asylum’s newly acquired property at Woodieliee, near Lenzie, located to the northeast of the city. The newspaper report states that as well as the majority of the inmates, omnibuses conveyed a considerable number of children with football being listed as one of the activities enjoyed by the party.14 Paisley Burgh Asylum enjoyed a similar arrangement during the latter part of the 1860s although their choice of location was Greenfield, not far from the Gleniffer Braes in Renfrewshire.15 At the Paisley Asylum excursion to Langbank in 1870 the article states that “Football, a pastime which many love, was well patronised, and dancing was engaged in by a few.”16

Football and the social elite

Beyond the importance placed on patronage by early football clubs, there is evidence to suggest that football was played by youths and young men from more advantaged backgrounds and from the ranks of the ‘socially mobile.’ There is evidence that football was played on the college green at Glasgow University decades before the time period that we are studying.17 As early as 1851 there is evidence to suggest that the university had a football club.18 That being said, the type of football activity being played at the university, as described by former students, certainly suggests that the games could involve large numbers with limited rules. For example, David Murray in his book, Memories of the Old College of Glasgow, quotes from the University Review of 1884, about the traditional games at the university and adds his own thoughts,

“Football continued to be played on the College green every session until 1870 when the migration to Gilmorehill took place. “It was a rough and tumble game in which the contending sides swept across the low green from Blackfriars Street to the New Vennel and back again like the hordes of Atilla.” This refers to 1855 and the few preceding years. It was the same in my time, 1857-65.“

Source: Murray, David; Memories of the Old College of Glasgow, 1927, P442.

An article from 1860, written by a former student, paints a somewhat different picture, hinting at a degree of skill with games being arranged between faculties on Saturdays.

“The Glasgow University, having extensive grounds attached to it, affords great opportunities for outdoor amusements, and students are distinguished there, not only for their knowledge of Greek and readiness in reply, but also for swiftness in the race and skill at foot-ball. Here, too, a rivalry exists between the students of Art and the students of Medicine: and well do I remember the Saturday matches, in which Art alternatively conquered and succumbed to Medicine.“

Source: Dunfermline Press, 27/03/1860, P4.

This latter description might fit in better with the story of Reverend James Barclay, born in Paisley in 1844 to a wealthy family, who attended the local grammar school before heading to Merchiston Castle School in Edinburgh, where he played rugby, and then onto Glasgow University. Barclay was described as being “captain of the Glasgow University cricket and football clubs at the university for some years” before graduating in 1865.19 An all-round sportsman, he would go on to become captain of the Gentleman of Scotland cricketers and was a notable pioneer of Association football in the south of Scotland where he played for the Dumfries and Canonbie Football Clubs.20

A decade or so before Barclay’s time at the university, some students native to Paisley and educated at Glasgow University, would go on to form the Paisley Football and Shinty Club in 1855. The social standing of the founders of the club is hinted at in the article which covers the inaugural meeting of the club, the Paisley Herald and Renfrewshire Advertiser stating that “the gentlemen present were not numerous, but very respectable.”21 At least three of the committee members would become legal writers, a fourth, David Brewster, was the nephew of notable scientist Sir David Brewster while others appear to be sons of Paisley’s wealthy merchant class. The club, which leased a field at Greenhill (not far from the current ground of St Mirren FC), mainly played internal matches but the article outlining the inaugural meeting does suggest that a game was being organised against the officers and men of the local militia, although it is not mentioned whether the game was to be football or shinty. The club appears to have been short lived as it only features in the local newspapers in 1855 and 1856 but it does present football as an organised sport a full decade before the emergence of the principal Rugby and Association clubs in Glasgow.

A read through the minute books of the Glasgow Academical Club, from the first meeting of 1866, provides an illustration of the high level of organisation behind one of the early powerhouses of the rugby game in Scotland. Established as a former pupils’ club, the inaugural set of minutes finely details the reasoning behind its creation which was influenced in part by the success of the older club at the Edinburgh Academy and by the fortuitous development of an area of land being leased by the Directors of the school for outdoor sports.22 Structures were quickly put into place with committees being created for the cricket and football teams. The West of Scotland Club provided strong opposition locally and the Glasgow Academical Football Club, as it came to be known, ventured out to the east to play the leading rugby football clubs in Edinburgh as well as the Edinburgh and St Andrews University clubs. By 1869 Glasgow University had its own rugby football club and within a couple of years additional opponents could be found in Glasgow as well as in Paisley and Greenock. In 1870 the Academical Club embarked on the first cross border tour, visiting Liverpool and Manchester, and two years later would emulate the West of Scotland Club by visiting Belfast to play the North of Ireland Club.23 With the obvious strengths of the club, in terms of its organisational ability and, more importantly, its on field success, there is perhaps little surprise that the Glasgow Academical Club would be so well represented within the early Scotland teams that faced England in the rugby football internationals.

Cricket and other sports clubs

Richard S. Young’s book, As the Willow Vanishes, provides a detailed account of the close association of cricket clubs in and around Glasgow with the development of many of the early football clubs. The associations are significant and far reaching. Cricket was organised as a sport much earlier than football in Glasgow. The oldest surviving club in the city is the Glasgow University Cricket Club which formed in 1829.24 When Queen’s Park FC were making the arrangements for the first official international match in 1872, they chose the West of Scotland Cricket Ground as the venue. When the Scottish Football Association was instituted in 1873 Archibald Campbell was elected as the first President. Archie, originally a native of Hawick, had founded the Clydesdale Cricket Club in 1848 and this club would successfully extend its influence into the sports of Association football, Rugby football and hockey. Clydesdale Football Club, formed in 1872, would oppose Queen’s Park FC two years later in the inaugural Scottish Cup Final.

Naismith’s Post Office Directory for 1878 lists the Hamilton Thistle Cricket and Football Club in its pages with a formation date of 1862. Very little is known, however, of the club although there are references in newspapers to cricket matches involving Hamilton Thistle from the late 1860s. The West of Scotland Cricket Club, which also formed in 1862, was, from the off, a major influence within the Glasgow cricket scene. According to Richard S. Young, ‘the West’ had ambitions to be a Scottish equivalent of the MCC in London.25 The founding of the club brought together businessmen under the patronage of Colonel Buchanan, a major supporter of cricket in the western districts of Scotland, whose own club Drumpellier, near Coatbridge, was an important sports club of the era. Buchanan was the first president of the new West of Scotland Club, a post he held until 1903. In 1865 an offshoot to the club was created with the formation of the West of Scotland Football Club. The new outfit would have had their own “in-house” playing rules but they were influenced by the emerging rugby code. The creation of the Glasgow Academical club in 1866, a natural early rival, and the arrival of W.H. Dunlop from Edinburgh in the same year would have firmly planted the rugby flag at the door of the West. Dunlop had previously been secretary of the [Edinburgh] Academical cricket and football clubs from 1864 to 1866. A number of other football clubs connected to cricket would follow the lead of the West of Scotland and play to the Rugby code.

However, as the Association game began to develop under the close watch of Queen’s Park FC a number of cricket clubs were drawn to this alternative game when establishing football sections. Ahead of Clydesdale FC was Dumbreck Football Club and Granville Football Club, both formed around 1871. A study of the earliest team lines available for the Granville Football Club connects a significant number of its players with the first and second elevens of the cricket club.

Another notable side which faced Queen’s Park in the late 1860s and early 1870s was the football section of Hamilton Gymnasium. The sports club had been formed in 1866, in part out of a wider campaign to establish a public park in the Lanarkshire town for outdoor sports. A report in the local newspaper states that,

“Now, however, something of a definite character has at last been resolved upon. From a paragraph in our local column, it will be seen that at a numerously attended meeting held in the Lesser Town Hall, on Tuesday evening last, the question of a public park was discussed. The meeting, which we understand, was most enthusiastic, were of opinion that the formation of a society for field sports, such as cricket, football, rounders, &c., would in the meantime, to a great extent supply the desideratum which has been so long felt. Accordingly, those present agreed to unite themselves under the title of “The Hamilton Gymnasium,” for the promotion of the objects indicated, and a provisional committee was appointed to carry out the necessary preliminary arrangements.“

Source: Hamilton Advertiser, 12/05/1866, P2.

Hamilton Gymnasium quickly got up and running; within a year of their formation the club recorded 95 members and by 1868 their list of honorary members included two local MPs, a Provost and Colonel Buchanan (of Drumpellier and West of Scotland cricket fame).26 Few details of the club’s membership survive but of those committee members who are recorded, they were local youths and young men who were mainly born within the town or within the county. Like many other of the emerging organisations, the footballers of Hamilton Gymnasium would have organised internal matches involving their members. Occasional games against other clubs like Queen’s Park did happen and were important but regular football activity was organised internally. This can be seen with the advertisement in May 1869 which states that “the Gymnasium is to be opened for the season on Monday evening, first, when cricket, football, and other manly exercises will, as usual, be provided.”27

Rifle Volunteer Movement

The Rifle Volunteer movement arrived in Britain in 1859 amidst concerns over an escalating European war and the perceived threat of a French invasion. The movement was very popular in Scotland, as elsewhere, and units were widely established over the course of the 1860s. Beyond military drills and shooting practise, wider sporting and social gatherings became associated with the movement. The most famous volunteer unit to be linked with Association football in Scotland was the Third Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers who were based in Glasgow and commenced as a Corps in 1859. The football club bearing the name was formed in 1872 and would go on to emerge as a major force in the Scottish game. Football as an activity, however, has an earlier place within the story of Third Lanark. For example, in 1866, when the volunteers were camped outside the village of Inverkip, there is evidence of football being enjoyed as a recreational activity…

“Near the beach, in front of the tents, a game at football is going on, and over the sward come the merry voices of young ladies who are moving about, slyly peeping underneath the canvas, and surprising some bashful young hero in his devotions to the culinary god.“

Source: Dundee Courier, 19/07/1866, P4.

The social side of the movement and the connections with football can also be found with the 16th Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers, Hamilton’s local volunteer corps. An annual picnic for the 16th LRV took place at Calderwood Castle in East Kilbride where football alongside racing and dancing were amongst the highlights of the outing.28 The village of East Kilbride, just a few miles to the south of Glasgow, had its own volunteer corps by 1867 who were instrumental in the establishment of an Association football club in 1871. The meeting to form the football club was called by Major Graham of Limekilns, who also led the 103rd LRV Corps. The captain of the football club was Private Alexander Warnock whilst Colour Sergeant Andrew Calderwood played in goal and Private Archibald Scott was a committee member. The connection can also be seen in 1873 with a social meeting in the Parish School room of what was now the East Kilbride Cricket and Football Club. The article commends the decoration on the walls…

“…while on the wall at the head of the room were arranged the cricket bats and football, supported on each side by a large bayonet star constructed by Sergt. J. Ramshaw, and kindly granted for the occasion by the 103d L.R.V.”

Source: Hamilton Advertiser, 12/05/1866, P2.

While many other volunteer corps would create football clubs in the months and years leading on from the notable football events of 1873, the 5th Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers Football Club, from Glasgow, were already undertaking regular football practise on Saturday afternoons at 3pm at their drill field by the end of 1872.29 Another volunteer corps, the 105th Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers, or Glasgow Highlanders, will be covered under the section devoted to migration.

Migration

Migration into Glasgow and the west of Scotland was significant over the span of the nineteenth century and accounts for much of the population rise. With insufficient welfare provision and often turbulent economic prospects the danger of destitution was a threat for many arriving in the large towns and cities. Associations and Societies rapidly sprang up in response, providing migrants with an opportunity to meet up and interact with people from their place of origin. This experience was not unique to Glasgow but the scale of this development was significant. In many respects these societies were mutual aid organisations as a major part of their existence was to support people if they fell on hard times in the city. The accompanying slides provide examples of the migrant societies existing in Glasgow from 1850 to 1872 and their geographic representation of Scotland as a whole. As well as being a provider of welfare, the societies also did much to promote and celebrate the traditions and cultures of their native land. There are examples linking some of these societies to the promotion of traditional sports, including football, within their activities.

Glasgow Celtic Society

The Glasgow Celtic Society was a hugely influential organisation within the city which supported people from the Highlands coming to Glasgow. Instituted in 1856 the society was established for,

“…preserving the language, literature, music, poetry, antiquities, and athletic games of the Highlanders of Scotland, for encouraging the more general use of the national dress, and also for establishing a fund for affording temporary relief to destitute and deserving Highlanders, and to assist worthy persons coming from the Highlands in quest of employment.”

Source: Stonehaven Journal, 12/02/1857, P2.

The promotion of traditional sports, which included shinty and football, was certainly a notable part of the activities of the organisation. The college grounds of Glasgow University, situated just off the high street, were originally used for the hosting of athletic games. Excursions also formed part of the wider activities of the Glasgow Celtic Society. In 1859 a gathering on the grounds of Elderslie House in Renfrewshire, which involved society members from Glasgow, Greenock and Port Glasgow saw games of shinty and football being played. Two matches at football were played with teams dividing into red badges against blue badges.30 The following year a special trip by steamer was made to Arrochar at the head of Loch Long. A field was provided so that a series of games could be enjoyed including “two games at foot-ball.”31

Glasgow Orkney and Shetland Association

From an early period of the nineteenth century migrants from Orkney and Shetland appear to have been arriving in Glasgow in large enough numbers to necessitate the formation of a dedicated society. The Glasgow Orkney and Shetland Benevolent Society was established as early as 1837 with the separate Glasgow Orkney and Shetland Association being formed in 1862. This latter organisation supported annual gatherings for its members which included sports. For example, in 1868 the Association organised a joint trip with their Edinburgh counterparts to Linlithgow where amongst fishing, boating and walks around the palace, a game of football was organised.32 The following year the Glasgow Association visited Lennoxtown to the north of the city where younger members of the excursionists enjoyed football as part of the activities.33 Beyond the specific events of the Orkney and Shetland Association in Glasgow, there appears to have been wider activities involving the migrant community. Over the course of the nineteenth century New Year’s Day in Orkney and Shetland was traditionally observed with ball games being enjoyed by communities across the islands. In 1866 Orcadians living in Glasgow organised and enjoyed a New Year’s Day football game on Glasgow Green. One newspaper concluded its brief report of the event by stating that,

“The old house associations seemed to kindle in every bosom, and the fun and frolic was kept up for upwards of three hours, when they returned to the city, highly gratified with the proceedings.”

Source: The Orcadian, 16/01/1866, P2.

Perthshire

Perthshire migrants were certainly active in football contests within the city, forming early football clubs based at Glasgow Green. One of the first opponents of Queen’s Park FC was the Drummond Club which was founded in 1869. This football club was formed by Perthshire migrants who wore Clan Drummond tartan caps. It is not known if the members of this early club were connected to the Glasgow Perthshire Society (whose name was later adopted by a junior football club which still exists today). However, they were linked to a branch of the rifle volunteer movement in Glasgow. In this case the 9th company of the 105th Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers, who were more commonly known as the Glasgow Highlanders. This volunteer regiment was formed in 1868 by Highland migrants in Glasgow and at its peak consisted of 12 companies. Football was already part of the recreational activity of the professional Scottish regiments. Indeed, a game in 1870 involving members of the Drummond Club and the football team of the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders provides evidence of the connections,

“A match at football was played in the King’s Park, Stirling, on Tuesday, between the members of the Drummond Club in connection with the 105th Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers and an equal number of the 93d (Sutherland) Highlanders. Three games were played, the first of which was finished in twenty-five minutes, the second in eighteen minutes, and the third in eight minutes, and all resulted in favour of the Glasgow Highlanders, the 93d having apparently not yet got into right condition for such a contest.“

Source: Scotsman, 09/04/1870, P7.

The matches between Drummond FC and Queen’s Park throw up an example of different football cultures. The Drummond Club played a rougher style of game which included tripping. Queen’s Park did not. The matches between both clubs proceeded on the agreement that tripping be banned.34

Callander

Football as an activity had an important cultural value in the little town of Callander and this would radiate south as the young people of the area migrated into the urban centres of the central lowlands. The area was renowned for the annual Handsel Monday football game, an activity which was slowly starting to decline but which continued to be observed throughout the period in question. Speaking in 1872 at the third annual reunion of the Natives of Callander and Vicinity Resident in Glasgow, the Chairman, Mr Robert McLaren, reminisced,

“…when I was a boy, I often heard it said that no district could compete, man to man, with Callander at the game of football… The practise of this manly game had fallen off considerably in our day. Yet we all remember how the sound of the bagpipe on Handsel Monday set all the village on tiptoe.“

Source: Perthshire Advertiser, 29/02/1872, P2.

As a child back in 1852 William McGregor, the future father of the Football League, attests to the reputation of Callander for football.

“A large house was being built for the late Earl Cairns at Duneira, Perthshire. The stone for this mansion had to be drawn a distance of twenty miles, and as a consequence the masons engaged on the work often had a little spare time. They amused themselves by playing football, and were fairly expert at the game, coming as they did from Callander, where the pastime had a hold.“

Source: Catton, J.A.H; The Real Football, London, 1900, P71.

The football experts from Callander certainly made an impression as migrants in Glasgow. By 1872 a Callander Football Club was playing matches on Glasgow Green. This club were the first opponents of Rangers FC in 1872 and took part in the inaugural Scottish Cup competition in 1873.

John Burns Connell

As mentioned earlier, Andy Mitchell, in his website article, covers the story of J. B. Connell. Dr Graham Curry also devotes some attention to this notable pioneer of football in Glasgow. Connell’s story deserves to be briefly covered here because it provides an example of the football journey of a migrant arriving in Glasgow. Connell was born at Doune in 1846 and raised on a farm near the Port of Menteith close to the town of Callander. As a youth he played in Callander’s famous Handsel Monday football game before arriving in Glasgow around 1863. In a retrospective account of his football career, he claimed to have brought the first football for public use to Glasgow. Players had to pay a fee for the upkeep of the ball before taking part.35 Connell was a member of the Thistle Football Club that played Queen’s Park FC in Glasgow’s first known challenge match under a form of the Association code in 1868. The date of Thistle’s origin is unknown, but they certainly appear to be well established by 1868. Connell’s connection with the club and the fact that they were based at Glasgow Green suggests that there could be a strong Perthshire connection. He was a founder member of the Drummond Football Club in 1869, a club of Perthshire migrants which, as has been stated earlier, had a connection to the 9th company of the 105th Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers (Glasgow Highlanders). An all-rounder, he was captain of the Glasgow Highlanders team which met the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders at Stirling in a game played under rugby rules in 1871.36 Connell features in some of the early games involving Callander FC, appearing in the earliest match reports dating from 1873 although the spelling of his name varies in some of the reports. He moved on to Eastern Football Club, a rising team based at Glasgow Green, and was rated highly enough within local football circles to be selected to represent Glasgow against Sheffield in 1875.

Argyllshire

Gary Ralston’s in-depth study of the early history of Rangers Football Club sheds a lot of light on the Argyllshire connections of the famous old club. Three of the four ‘founding fathers’ of Rangers came from the village of Rhu at Gare Loch. Another early member, Tom Vallance, a future Scotland internationalist, was also from the Argyllshire village. Only a few months before the formation of the club at Glasgow Green, Rhu had hosted its annual athletic games. The event, which featured traditional games like foot races, putting the stone and the high jump, took place on New Year’s Day 1872 and culminated with a game of football.37 By March 1872 the brothers Moses and Peter McNeill along with Peter Campbell, all natives of Rhu, were setting up their football club which they named Rangers. A fourth founder was William. H. McBeath, a native of Callander, who was a neighbour of the McNeills and lived in the same tenement block at 17 Cleveland Street.38 McBeath looks to have played for the Callander Football Club, appearing alongside J. B. Connell in the earliest known team lines for that club in 1873. What is particularly notable about the early formation of what would become a future giant of the Scottish game were the young ages of the founders. Moses was 16 years old, his brother Peter was the oldest at 17. Peter Campbell and William McBeath were just 15 years old. This illustrates similarities with the experience of some of the other clubs highlighted in this study and demonstrates the desire for youths, in some cases not long out of school, to continue enjoying football as a recreational activity.

Morayshire and Aberdeenshire

The final example relates to Queen’s Park FC, a club which would be regarded as the ‘senior’ or ‘premier’ of the clubs playing to the Association code in Scotland due to their influence in the early development of the game. Richard Robinson’s history of the club, first published in 1920, provides a useful insight into the early years while Andy Mitchell has delved even deeper into the story of the original pioneers with his website article entitled Football’s Founders from Fordyce. Many of the early founding fathers of the club were from the north of Scotland, particularly around Morayshire and neighbouring Aberdeenshire. As Andy Mitchell establishes in his article, three of the founders went to the same school, Fordyce Academy in Aberdeenshire. The first of these scholars was William Klingner who was born at Portsoy in Banffshire. The remaining two were brothers, Robert and James Smith, who were originally from Morayshire. Other notable northern members of the Glasgow outfit included Donald Edmiston who was originally from Aberdeenshire, Lewis Black, who was born in Cullen, and James C Grant who originally hailed from the village of Duthil in Speyside. The geographic connections are reflected in the naming of the club. The contending names initially were The Northern, Morayshire and The Celts. When an agreement could not be reached Mr Grant suggested going with Queen’s Park in recognition of the local public park and this narrowly won through after a series of divisions by a single vote.39 There were members from Glasgow and other parts of Scotland that served on the committee but the northern representation running from Morayshire across to Aberdeenshire appears to have been particularly important at the earliest stage of development. The wider story of the club is well documented and its importance in the emerging Association game in Scotland has been covered in many publications. From the humble early days of playing matches on the Queen’s Park recreation ground, the club would go on to organise the first official international match in 1872, providing the Scotland team from within its own membership. The club organised the meeting that created the Scottish Football Association and instituted the Scottish Cup in 1873 and built Hampden Park, Scotland’s first purpose built Association football ground. Through their influence, the distinctive playing style of the club would quickly develop into a Scottish style which would go on to influence the game of football far beyond the borders of Scotland.

Irish Immigration

Irish immigration into the city of Glasgow and the leading towns of Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire was significant over the course of the nineteenth century. The experience of those arriving could differ greatly. Many Irish Protestants, coming from the Ulster Scots tradition, shared religious values and ancestral links with much of the native Scottish population of the Lowlands and were able to assimilate more easily into society. Irish Catholics, to the contrary, did not have a smooth transition into Scottish society. Religion was at the centre of the friction, but perceived cultural differences and racial stereotyping were also factors. Irish Catholic immigration into Scotland existed prior to the 1840s but the Great Famine, which ran from 1845 to 1852, substantially increased the number of immigrants arriving in Glasgow and at many other communities across west central Scotland. Hostility and open discrimination existed and large sections of the Irish Catholic community in Scotland were crowded within the worst slum conditions in the expanding towns and cities. The formation and integration of a football club of Irish Catholics into Scotland’s developing Association game during the late 1860s and early 1870s therefore stands out as being notable. The club in question was formed in 1868 and initially played on ground at the Rochsoles estate in Airdrie.40 A retrospective article entitled Memories of Football in Airdrie, which appeared in the Airdrie and Coatbridge Advertiser in 1945, suggests that the owner of the estate, Major Archibald Gerard, who was a prominent member of the Catholic faith, looked sympathetically on the requirements of the new club.41 The Rochsoles estate, two years earlier, had hosted an excursion, which included games of football, involving the sabbath schools associated with St Margaret’s Christian Doctrine Society, a Catholic organisation connected to the local church in Airdrie.42

The club was named Airdrie Football Club and would become a member of the Scottish Football Association. Although they do not appear as a member club for season 1873-74, they are listed as a member by the time of the publication of the first Scottish Football Annual in 1875. Airdrie were nicknamed the ‘Hammer Drivers’ and were one of the first clubs to play against Queen’s Park when both sides met in home and away matches in 1870. Like many other clubs of the period, in the era before the universality of playing rules, Airdrie had their own views on how to play the game. As with the game against Thistle FC in 1868 and Drummond FC in 1870, Queen’s Park had to negotiate although the 1945 article, quoting from an unknown source, states that the first match of 1870 was played under “London Association Rules.”43 Hibernian Football Club, formed in Edinburgh in 1875, would face discrimination at the hands of the Scottish Football Association not long after their formation when they were initially denied membership as they were deemed to be, to all intents and purposes, a ‘foreign’ club. There is no evidence to suggest that Airdrie experienced this type of discrimination when it applied to become a member club of the same Association. This may have been down to something as simple as their choice of name. Hibernian of Edinburgh would become the first great Irish immigrant football club of Scotland and were an inspiration for the dozens of clubs that followed in their wake. The story of the Irishmen from Airdrie, however, is notable as it indicates that immigrants were involved from the very earliest period of the fledgling Association game in Scotland.

Adverts for football equipment and football grounds

With significant football activity being recorded among a variety of organisations across the city of Glasgow and the connected communities in Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire, there had to have been evidence of commercial enterprises to meet with the demand. Whilst, unlike Edinburgh, there does not appear to be a dedicated sports outfitter in Glasgow prior to 1873, there were numerous retail outlets where footballs could be purchased. During the 1860s adverts for footballs at the Royal Polytechnic Warehouse in Glasgow’s Jamaica Street appeared, not only within Glasgow newspapers, but within newspapers covering Paisley, Greenock and Stirling.44 A rival Glasgow store, Wilson and Matheson’s Retail Department based in Glassford Street were also advertising footballs by 1861.45 In 1869 T.C. Barlow’s of St Vincent Street in Glasgow, no doubt looking at the bustling summer excursion market, were advertising for sale or hire, amongst other things, 120 tents and marquees, 400 skates and 20 footballs.46 Glasgow’s Reid & Company, in 1870, were promising newspaper readers that they were “…the place for cricket bats, croquet, foot-balls &c…”47 Towards the end of the period Millar’s Family Hat Warehouse in Glasgow’s Queen Street were advertising, among an assortment of other headwear, cricket and football caps.48 It is perhaps fitting that the employees of John Leckie & Co, Saddlers from Glasgow, who were enjoying a game of football during their work outing to Largs in 1868, would, judging from subsequent newspaper adverts, be busily engaged in producing footballs, “Association and Rugby,” in the months that followed on from the international football match at Partick in 1872.49

Towards the end of the period there is evidence of adverts being placed for renting football grounds. In 1870 an advert appeared in the Glasgow Evening Citizen, placed by an anonymous football club, appealing for a ground in the vicinity of the New City or Great Western Roads.50 The following year an area of land was being advertised to “cricket, football or bowling clubs” near Queen’s Park on the southern edge of the city.51 In 1872 another advert appeared in the Glasgow Herald. The advert simply stated “Park wanted for Foot ball; use on evenings and Saturday afternoons. State terms…”52

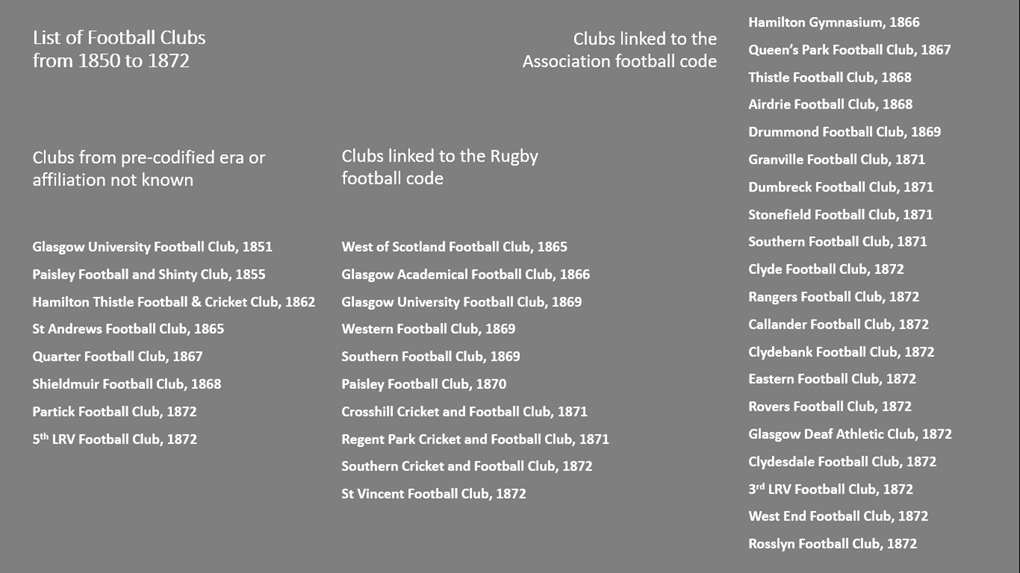

List of clubs

The following slide provides a list of football clubs for Glasgow and the surrounding localities which are covered in this paper for the period running from 1850 to 1872. They have been referenced either in contemporary articles or in retrospective accounts. Checking and verifying the dates of early football clubs, from personal experience, can be very difficult. A number of clubs, for example, bearing the name “Southern” appear in the early newspaper reports and football annuals with varying years of formation given. One of them even claimed to play to both the Association and Rugby codes and it is possible that this club has been duplicated within the lists. Other clubs have different years of formation listed in the football annuals from one year to another making the task a challenging one. With a few of the examples almost nothing exists other than a solitary reference whilst others have plenty of material to support the claim for their foundation year. Many of the clubs do not appear to have lasted very long, but this can be said of many clubs in the immediate years following on from 1873.

Conclusion

The four-month period leading on from the staging of the first official international match at Partick witnessed the beginnings of the rapid rise of Association football across Glasgow and the surrounding communities of west central Scotland. The formation of the Scottish Football Association in March 1873 and the institution of the Scottish Cup tournament brought the necessary organisation and focus that the game would need as new clubs started to form. Queen’s Park Football Club, without question, was the driving force north of the border during the formative years. The subsequent rise of the Association game is all the more dramatic when contrasted with the first few humble years of the club’s existence, arranging matches between members on the recreation ground at Queen’s Park and seeking out opponents. The rugby football game in Glasgow certainly had an edge over their Association counterparts during the late 1860s with the West of Scotland and Glasgow Academicals having access to strong competition from the numerous clubs in Edinburgh and the east of Scotland as well as the formation of clubs closer to home. The future success of the Association game in Glasgow lay in its working-class foundations. A game that could pair Queen’s Park FC against a team of Perthshire migrants, in the Drummond Club, or a team of Irish immigrants, in Airdrie FC, was one that could appeal to much wider sections of society than the emerging rugby game which had a closer association with students from the universities and former pupils from the leading grammar schools and academies. The first international football match in Partick was the spark that ignited the powder keg because it put Association football firmly on the centre stage in Glasgow, appealing to a largely working-class audience, who not only possessed an appetite for the game but had a working knowledge of it.

References

1. Scottish Football Annual, 1875, P7.

2. David Stow’s tract on Physical and Moral Training, quoted in Fraser, William; Memoir of the Life of David Stow, London, 1868, Pp120-5.

3. Greenock Advertiser, 16/05/1871, P2.

4. North British Daily Mail, 07/06/1852, P2, Glasgow Constitutional, 18/05/1853, P2 and Paisley Herald and Renfrewshire Advertiser, 19/06/1869, P4.

5. Paisley Herald and Renfrewshire Advertiser, 19/06/1869, P4, Hamilton Advertiser, 08/08/1863, P2 and Airdrie and Coatbridge Advertiser, 11/08/1866, P2.

6. Glasgow Herald, 25/07/1863, P8.

7. Glasgow Herald, 20/05/1862, P1.

8. Glasgow Morning Journal, 08/05/1862, P1.

9. Glasgow Herald, 14/08/1867, P5, Paisley Herald and Renfrewshire Advertiser, 04/08/1860, P2 and Hamilton Advertiser, 12/08/1871, P2.

10. Glasgow Herald, 25/06/1861, P2.

11. Paisley Herald and Renfrewshire Advertiser, 11/09/1869 and Hamilton Advertiser, 06/05/1871, P2.

12. Dundee Advertiser, 12/01/1869, P4.

13. Reports from Commissioners: (16). Lunacy; (Scotland). Session 19/11/1867 – 31/07/1868, Vol 31, P172.

14. Glasgow Herald, 09/09/1871, P4.

15. North British Daily Mail, 02/07/1869, P3.

16. Paisley Herald and Renfrewshire Advertiser, 02/07/1870. P1.

17. Murray, David; Memories of the Old College of Glasgow, 1927, P535.

18. Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 06/04/1851, P6.

19. Sulte, Benjamin; A History of Quebec, Its Resources and People, Vol II, Montreal, 1906, P629.

20. Glasgow Herald, 11/12/1876, P6.

21. Paisley Herald and Renfrewshire Advertiser, 24/11/1855, P4.

22. Minute Book of the Glasgow Academical Club, 1866 – 1878, Glasgow Academy Collection.

23. Glasgow Herald, 08/01/1872, P5.

24. Young, Richard S; As the Willow Vanishes, Consilience Media, P78

25. Young, Richard S; As the Willow Vanishes, Consilience Media, P39.

26. Hamilton Advertiser, 21/09/1867, P2.

27. Hamilton Advertiser, 01/05/1869. P2.

28. Hamilton Advertiser, 03/08/1872, P2.

29. North British Daily Mail, 21/12/1872, P1.

30. North British Daily Mail, 21/02/1859, P2.

31. Scottish Banner, 07/07/1860, P4.

32. Orkney Herald, 09/06/1868, P3.

33. Glasgow Courier, 02/05/1861, P1.

34. Robinson, Richard; History of the Queen’s Park Football Club, 1867-1917, Glasgow, 1920, P36.

35. Capel-Kirby W. & Carter F. W.; The Mighty Kick; The History, Romance and Humour of Football, London, 1933, Pp 194-5.

36. Falkirk Herald, 13/04/1871, P3.

37. Greenock Telegraph and Clyde Shipping Gazette, 03/01/1872, P3.

38. Ralston, Gary; the Gallant Pioneers, DB Publishing, P109.

39. Robinson, Richard; History of the Queen’s Park Football Club, 1867-1917, Glasgow, 1920, P12.

40. MacArthur, John; New Monkland Parish, Glasgow, 1890, P408.

41. Airdrie and Coatbridge Advertiser, 13/10/1945, P11.

42. Airdrie and Coatbridge Advertiser, 04/08/1866, P2.

43. Airdrie and Coatbridge Advertiser, 13/10/1945, P11.

44. Glasgow Herald, 14/12/1860, P1, Paisley Herald and Renfrewshire Advertiser, 06/07/1861, P8, Greenock Advertiser, 27/12/1866, P1 and Stirling Observer, 11/07/1861, P4.

45. Glasgow Saturday Post, and Paisley and Renfrewshire Reformer, 06/07/1861, P5.

46. Glasgow Evening Citizen, 10/07/1869, P1.

47. Glasgow Evening Citizen, 21/05/1870, P1.

48. Glasgow Herald, 13/06/1872, P1.

49. Glasgow Evening Citizen, 17/08/1868, P3 and North British Daily Mail, 04/12/1873, P8.

50. Glasgow Evening Citizen, 22/03/1870, P1.

51. Glasgow Herald, 08/03/1871, P3.

52. Glasgow Herald, 29/07/1872, P1.

Dear sir

I am here in america.my father was from Dunbarton.his father named John Cameron won metal’s for football.i have 1.iT is dated 28-32 Scottish intermediate football league. Can you get me any info on my grandfather.PLEASE.MY E MAIL ISianc24410@gmail.com

Thank you

LikeLike

Hi Ian, thanks for getting in touch. I will pass your request onto the staff at the Scottish Football Museum. Hopefully we will have a positive update for you soon!

LikeLike

Richard, I thoroughly enjoyed reading your article and its evidentiary references. Having covered certain aspects of your research in my own studies I feel that one of the most challenging aspects in finding clarity of understanding when reading such historical references is that of context. What exactly was meant by foot-ball in the context of pre-1872 references?

As you acknowledge, there were occasions of clubs negotiating rules prior to playing. Even the reading of newspaper reports on matches into the early 1870s , listed under the heading ‘football’, required finding words such as ‘goalkeeper’ of ‘try’ to determine which code of football was actually being described. It took some time before a match description might be preceded by the heading ‘football (rugby)’ or ‘football (association)’ — and this was in the era when such a distinction had been drawn.

There is a published list of ninety-one ‘Local Football Matches’ in an 1875 Glasgow Herald to be played between the months of September and December. Many, on closer examination, prove to be neither local nor of football as we would understand the word. Instead, there are games listed as far distant as London, and several between clubs known to be practitioners of the rugby code. Yet all were classified as ‘football’

In the earlier days, ‘foot-ball’ might involve any combination of rules and skills wherein a ball was kicked as part of the general completion of the activity; whether or not handling, rucking or scrimmaging was also included. This lack of clarity was further exacerbated by scoring systems that meant no matter whether a game was played more towards association or rugby rules; a scoring point was called a ‘goal’ and earned by kicking the ball through the designated posts. The early value of a touch-down was simply to earn a ‘try’ at goal. if a match report specified merely the scoring of a goal, then the code of play would remain uncertain.

With regard to advertisements, the selling of a ‘foot-ball’ falls under the same uncertainty. An association ball would be crudely made and crudely shaped. Similarly for a ball used within the rugby code. Methods of mass production and dimensional purity were a long way off. Given the other aspects of crossover and uncertainty already mentioned, I would hazard a guess that the pre-1870’s sale of foot-balls would have provided the purchaser with an object that was capable of use within whatever form of kicking game was being pursued.

Best regards

LikeLike

Hi Brian, great to hear from you. I fully agree, it can be a bit of a minefield. I tend to view the early matches connected to the principal codes as being variations. The Association code in particular was so basic initially as to require teams to discuss some of the finer details. In the early years Queen’s Park move from 20 a side in one game to 10 a side in another. Even if they are to a similar framework of rules, the difference in numbers would impact greatly on the way that games were played. True uniformity in the rules and in the equipment wouldn’t happen until long after this early period. For the rugby and association codes it could be argued that it is as late as 1886 when the respective international boards are formed.

LikeLike

Really interesting, thanks for taking the time to research and write that.

LikeLike

Thanks John!

LikeLike