Introduction

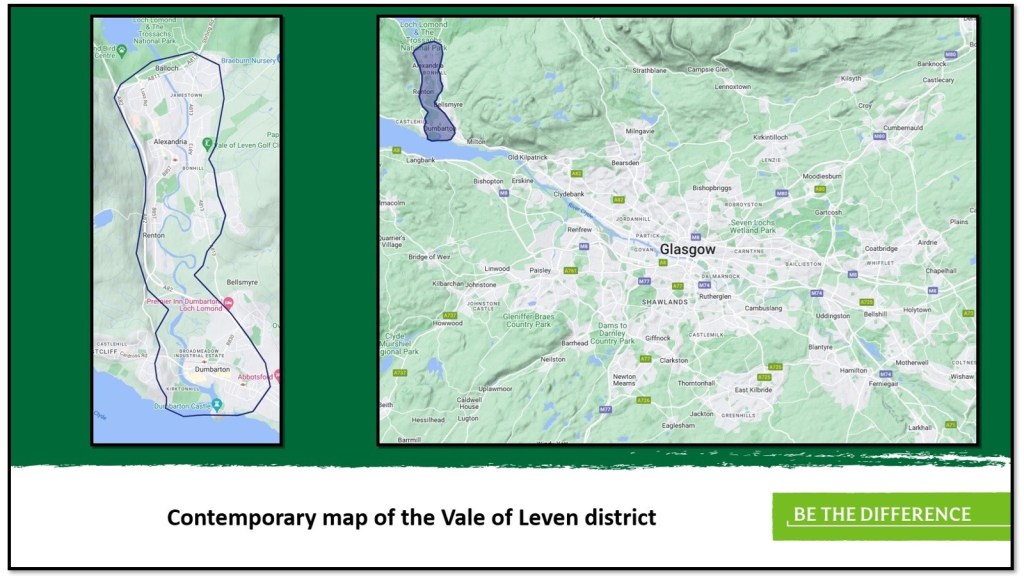

The Vale of Leven district is situated within West Dunbartonshire and lies approximately 13 miles to the northwest of Glasgow as the crow flies. The valley itself is about five miles in length and follows the River Leven on its journey from Loch Lomond in the north down to Dumbarton where it becomes a tributary to the River Clyde.

The significant growth of the local textile industry by the mid nineteenth century resulted in an expansion of the local population. Migration, particularly from the Highland region of Scotland and from Ireland, was vital in helping to provide the local print works and dye works with an adequate supply of labour. By 1871 the main urban settlements within the district accounted for approximately 23,159 people.[1] This population was well served by an established rail network. As early as 1858, an existing line running from Dumbarton to Balloch was connected to the new Glasgow, Dumbarton and Helensburgh line.

[1] Issac Slater’s Royal National Commercial Directory of Scotland (1886), 1058, states that the population of Dumbarton in 1871 was 11,429 while the urban population for the rest of the Vale of Leven district is calculated by Charles Docherty as being 11,730 in 1871 – see Docherty, C. (1981) The growth of the Vale of Leven 1841-1891. MLitt thesis, 116.

The introduction of Association football to the Vale of Leven

The first of the clubs, Vale of Leven FC, was formed in Alexandria on 20th August 1872. It was Glasgow’s leading side Queen’s Park FC which convinced the new club to adopt the Association game.[2] The first of a series of matches between Queen’s Park and Vale of Leven took place on 21 December 1872. The Glasgow side had already given up its hybrid version of the Association rules, adopting the Laws of the Game in full, and Vale of Leven was introduced to an innovative brand of football designed to work effectively within the constraints of the three man offside rule. Author John Weir, in his book, The Boys of Leven’s Winding Shore, states that the second match, played on 11 January 1873, ended in a 0-0 draw as “the play had to be stopped on several occasions so that Queen’s Park could explain some of the finer points to the inexperienced Levenites.”[3] In the third game, played in Glasgow on 15 February 1873, a notable example of the systematic approach of Queen’s Park is provided in the Glasgow Herald article which describes a five man passing move, “Messrs Gardner, Leckie, Wotherspoon, Taylor, and M’Kinnon working beautifully to each other’s feet.”[4] Other clubs were starting to form towards the end of 1872. The earliest history of Dumbarton FC, written in 1883, claims the very end of 1872 as its starting point.[5] Whilst Renton’s exact date of formation is less clear what we can say with certainty is that by 1873 they were one of at least nine association football clubs existing in the district.

[2] See Robinson, Richard (1920) History of the Queen’s Park Football Club, 1867-1917. Glasgow: Hay Nisbet & Co. Ltd, 38-9.

[3] Weir, John (1993) A History of Vale of Leven Football Club. The boys from Leven’s winding shore. PM Publications, 4.

[4] Glasgow Herald, February 15, 1873, 7.

[5] Son of the Rock (1883) The Dumbarton Club. In: McDowall, John. ed., Scottish Football Annual, Glasgow: W. Weatherstone & Son, 74.

A socio-economic analysis of early footballers from the Vale of Leven district

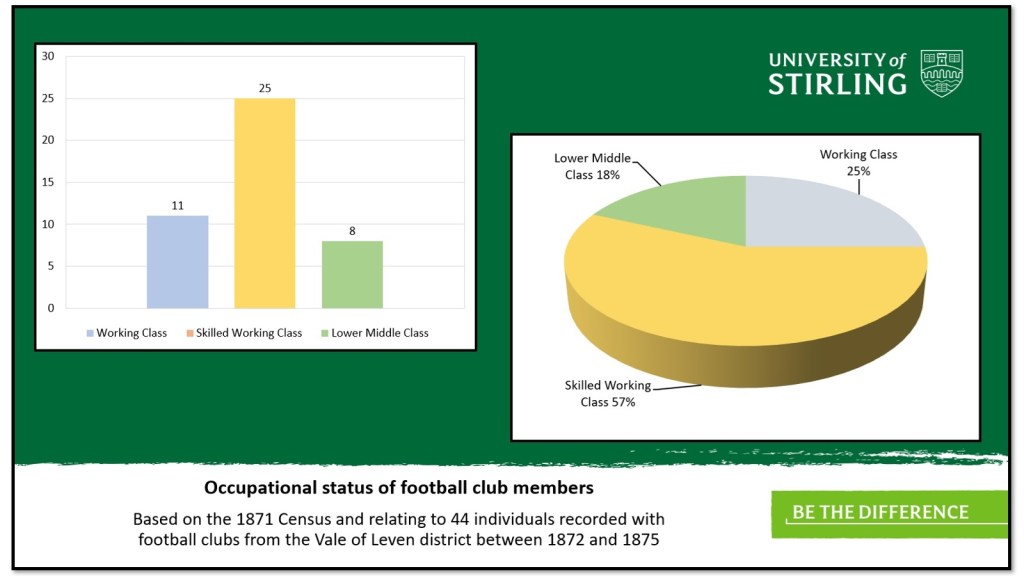

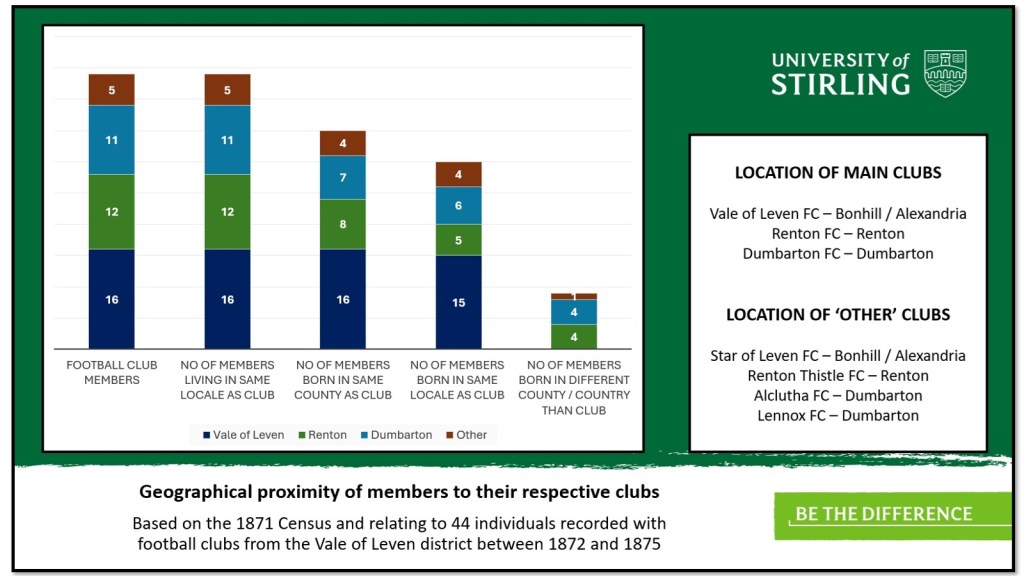

As part of this presentation, a study was undertaken of 44 football club members from the Vale of Leven district between 1872 and 1875. This was done to get a better understanding of the socio-economic status of the club members by identifying their occupations as well as finding out where they lived and where they had been born. A large majority of the club members are linked to the three main clubs (Renton, Dumbarton and Vale Of Leven) with just five of the sample coming from other clubs. This is mainly down to the difficulty of tracing early team information for club members outside of the “big three”.

As can be seen from both graphs, the single largest composition of football club members are from skilled working-class backgrounds. This category covers ship joiners, dyers and calico printers. Following on from this, the next largest category relates to semiskilled working-class occupations. This group included a variety of labourers working in the textile industry and in the shipyards, including dye wall labourers, print field workers and shipyard labourers. The final group accounts for lower middle-class occupations. Most of these members were employed as clerks in a variety of positions. Taken as a whole, the number of football club members that come from working class backgrounds is very significant and highlights the involvement of the working class in the Scottish game at such an early period.

This graph identifies where the football club members were born as well as where they were living by the time of the 1871 Census. The first column sorts the individuals into their affiliated clubs. The second column confirms that all 44 members were based in the same locality as their respective club from at least the time of the 1871 Census. There was therefore no need to commute any distance to visit their club ground. The third column looks at the number of members born in Dunbartonshire. It can be seen that for the Vale of Leven club, all of the players were born in the county while four members of Renton FC and four from the Dumbarton club were born outside of the county. The fourth column relates to players born in the same locality as their club. For Vale of Leven FC, 15 of their members were born in Bonhill or Alexandria with a 16th member born in the village of Balloch, a little over a mile to the north. The final column shows that nine of the 44 members in the study were born outside of Dunbartonshire. Two of the Renton members were born in Ireland while the birthplace of the remaining club members in this column covers different parts of Scotland, from the vast Highland region to the lowland districts of Glasgow and Renfrewshire.

Brief background to the three leading clubs

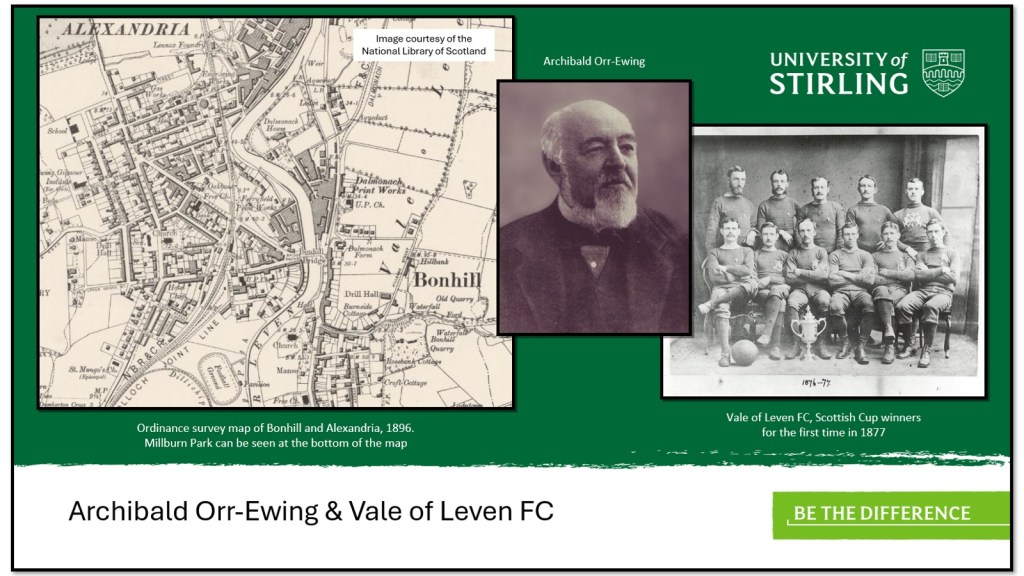

As mentioned earlier, the Vale of Leven district was a major centre for the dying and calico print industry. Local magnates like Alexander Wylie in Renton and John and Archibald Orr-Ewing in Alexandria and Bonhill were dominant figures. Matt McDowell argues in his PhD thesis from 2010, that “Sport in the Vale was co-opted by the didactic regimes of Alexander Wylie and the Orr-Ewing family as a means of creating solidarity and respectability amongst its workforce”.[6] The dye works most closely connected to Archibald Orr-Ewing in particular supported the rise to prominence of Vale of Leven FC. Early on, the football club was able to secure access to a local field before opening a ground at North Street Park. A more permanent home was found in 1888 when the Vale occupied Millburn Park. The Vale of Leven players were also excellent at shinty, and the club would win the Glasgow Celtic Society Cup in 1880.

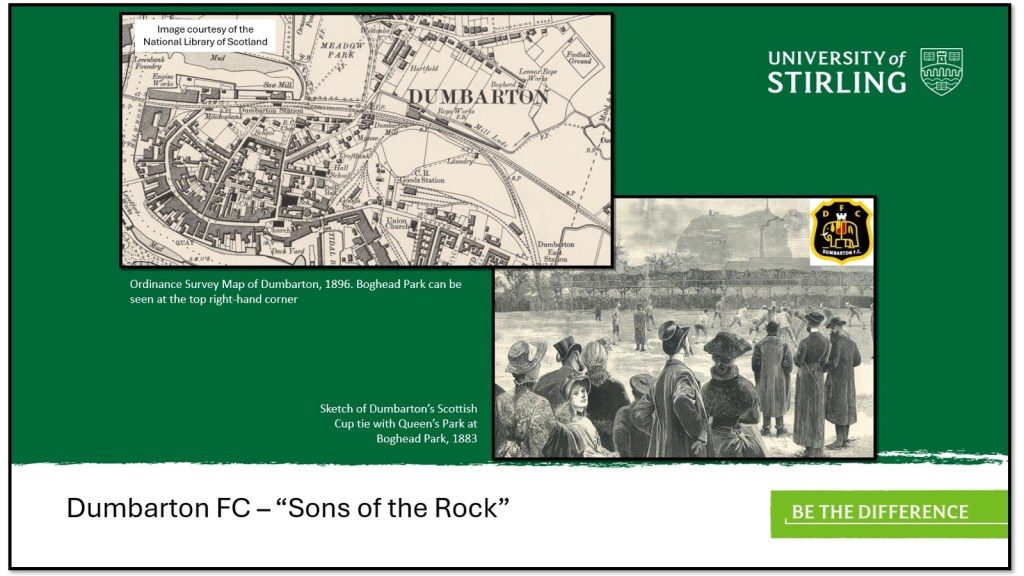

The coastal town of Dumbarton, comfortably the largest population centre within the study, provides a more diverse spread of occupations. Dumbarton’s waterfront was dominated by its trademark volcanic rock as well as by the local shipbuilding industry. While the latter industry accounts for a significant number of workers connected to the local football club, other occupations include law clerks and cabinet makers. The earliest history of the club suggests a strong shinty influence amongst the early founders.[7] For a period, Dumbarton FC were based at Townend, not far from Dumbarton Central Station, but made the short move to Boghead Park in 1879.

Renton FC depended on the patronage of Alexander Wylie and the Dalquhurn Dye Works. The Dalquhurn factory was a major source of employment within the village. Wylie was a senior partner within the company which was owned by William Stirling & Sons. The close relationship between the club and the factory can be seen in the memo from 1888. In this note, the factory manager apologises for the lack of consultation in the laying of a pipe running from the factory to the football ground. He reassures the club officials that the ground will be returned to its former condition. The dye works was an important local employer but some club members were employed in the boatbuilding industry of Dumbarton further to the south. Renton originally played at South Side Park, at the southern edge of the village before moving to Tontine Park in 1878. As with the Dumbarton and Vale of Leven clubs, shinty was the established sport in Renton and was played by members of the football club.

[6] McDowell, Matthew Lynn (2010) The origins, patronage and culture of association in the west of Scotland, c. 1865-1902. PhD thesis, 68.

[7] Son of the Rock (1883) The Dumbarton Club. In: McDowall, John. ed., Scottish Football Annual, Glasgow: W. Weatherstone & Son, 74.

Domestic record of the three leading clubs

A good indicator of the relative success of the three main clubs is their achievement in reaching major cup finals. In Scotland, two trophies in particular were much sought after. Overall, the Scottish Cup was the most important competition and the three clubs collectively appeared 16 times in the 17 finals between 1875 and 1891. The other prized piece of silverware was the Glasgow Merchant’s Charity Cup. This competition was invitational and involved a limited number of clubs, but it is a mark of the importance of the three clubs that they were regularly asked to compete. In the 13 finals between 1878 and 1889, the three clubs were represented on 10 occasions.

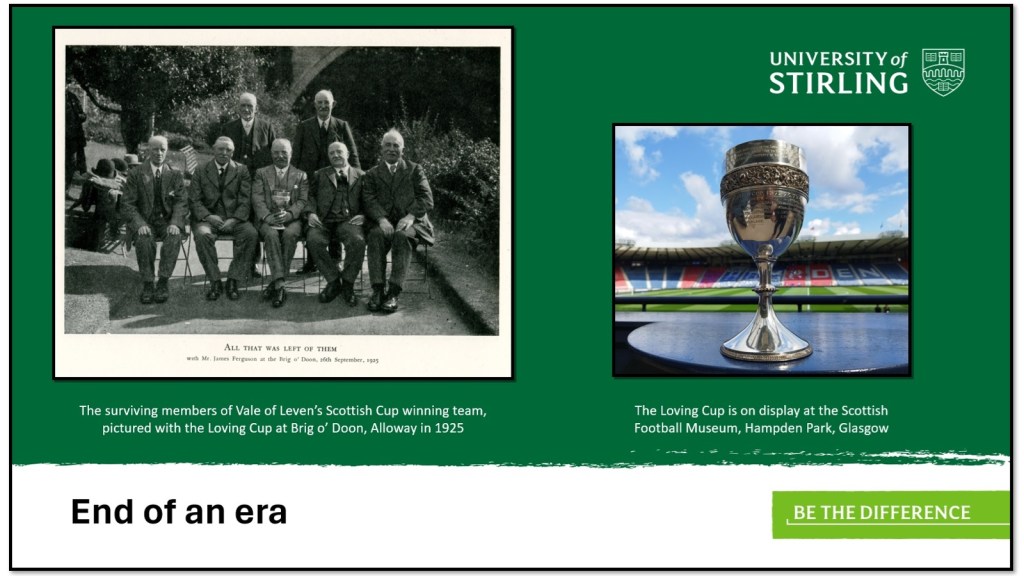

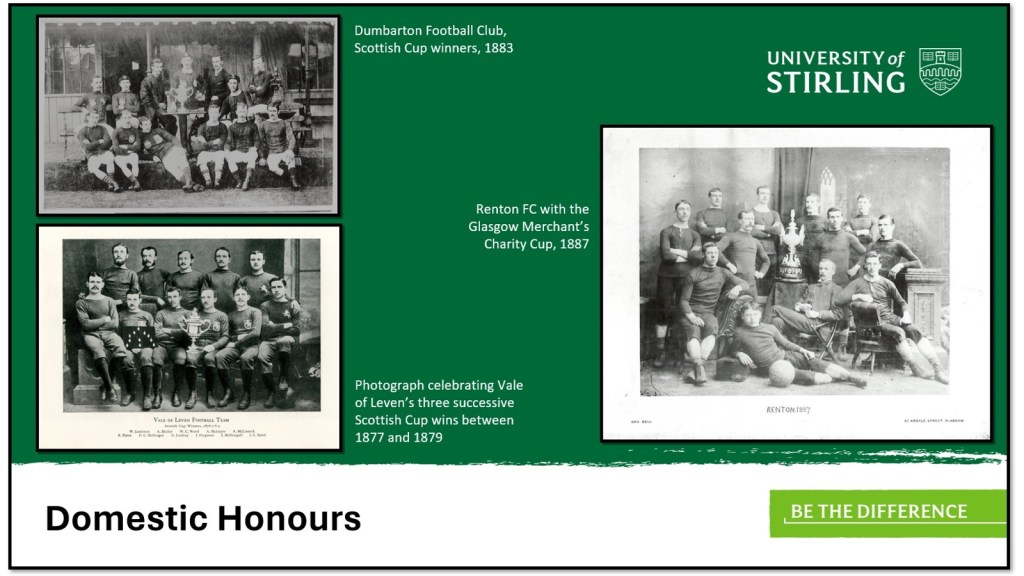

The three clubs enjoyed specific periods of success. For the Vale of Leven club, the mid to late 1870s saw the club reach its peak. The Vale became the first club to defeat Queen’s Park FC when they won a controversial Scottish Cup tie at Hampden Park by two goals to one in 1876. From that noteworthy achievement they would go on to win the trophy three years in succession. On the back of their success a silver chalice, referred to as the Loving Cup, was presented to the 17 players who had played across the three finals. For many years the Loving Cup became a focal point for annual gatherings, with the old players meeting up to reminiscence about their sporting achievements.

Whilst Renton would contest a Scottish Cup final as early as 1875 and as late as 1895, the main period of success for the club was the mid to late 1880s. Renton would contest three Scottish Cup finals in four years, winning the trophy in 1885 and 1888. The first of these finals saw the club defeat local rivals Vale of Leven. The latter final, a 6-1 victory over Cambuslang, is still a record victory in the Scottish Cup final although Celtic equalled this score line against Hibernian in 1972. Renton also had a fantastic record in the Glasgow Merchant’s Charity Cup, winning the trophy four years in succession between 1886 and 1889.

Dumbarton enjoyed two periods of success during this era. The first came in the early 1880s when the club contested three Scottish Cup finals in a row between 1881 and 1883. That latter year saw the “Sons of the Rock” finally lift the trophy with a 2-1 win against Vale of Leven. The early 1890s were also a period of success. In 1891, the Scottish Cup final would be reached once more and the first of two League championship titles was claimed. This first title was shared with Rangers but Dumbarton would be crowned outright champions the following season, finishing the 1891-92 campaign 2 points ahead of nearest challengers Celtic.

The Football Championships

By the late 1870s, English and Scottish clubs were routinely organising matches against each other. Of particular interest was the contest between the holders of the respective national cups. On 13 April 1878 Vale of Leven lined up against Wanderers at the Kennington Oval in London. The Wanderers had won the FA Cup three years in succession while The Vale had claimed the Scottish Cup for the previous two years. The match ended in a 3-1 victory for the Dunbartonshire club. This was followed with home and away matches against Old Etonians, the FA Cup winners of 1879. The Vale, by now Scottish Cup winners for a third year in a row, came out on top in both matches, winning 5-2 in Glasgow and 2-1 in London. As with the Wanderers game, these matches highlighted the notable difference in tactics and playing styles. They also highlighted a gulf in social status; a team of block printers, printfield workers and tinsmiths opposing gentleman footballers of the social standing of Lord Arthur Kinnaird, Alfred Lyttleton and Major Francis Marindin. While the success of Blackburn Olympic over the Old Etonians in the FA Cup final of 1883 is understandably acknowledged as a watershed moment for association football, the notable achievements of the Vale of Leven club a few years earlier has received less attention.

By the time Dumbarton, as Scottish Cup winners, faced FA Cup holders Blackburn Olympic in 1883, the game was being referred to as the “Championship of the United Kingdom”. Again, home and away games were organised. The first match was played at Hampden Park in Glasgow on 1st September 1883 and ended in a 6-1 victory for Dumbarton. The return fixture played in Lancashire on 23rd February 1884 saw Olympic avenge their earlier defeat with a 4-3 victory.

In the contest of 1888, when Renton faced West Bromwich Albion, the stakes appeared to be even higher. The press referred to this game as being the “Championship of the United Kingdom and the World”. The match took place at 2nd Hampden Park on 19th May 1888 under trying conditions. Heavy wind and rain forced a 10 minute delay in the first half but the match was played to a finish. Renton would run out 4-1 winners, scoring three goals in the second half.

The legalisation of professionalism in England and its consequence for Dunbartonshire clubs and players

The legalisation of professionalism in England had a major impact on the game south of the border, but the decision also created major challenges for the game in Scotland. The steady flow into the midlands and north of England of primarily working-class footballers from Scotland was facilitated by football agents. The agents were used by professional clubs to entice footballers with the lure of playing football for more money than they could earn back home working in full time employment.

Dunbartonshire was a natural draw for football agents but the risk of being caught was significant. In 1885 a Burnley agent was trapped inside a public house in Dumbarton, surrounded by a baying mob in excess of 500 people. He was eventually let go on the promise never to return and was warned that he would be tarred and feathered if he was ever seen again.[8] By 1888 the number of agents arriving in Scotland was described in the press as being an infestation.[9] A “vigilance committee” was established in Dumbarton which was handed the task of uncovering and apprehending football agents.[10]

The Scottish Football Association, reacting to the exodus of players out of Scotland, banned “Anglo-Scots” from playing for the national team. As a result, at the stroke of a pen, the Scotland national team lost many of its finest players. The ban had an impact on players like Alex Latta. Described as a boatbuilder to trade, Alex had come to prominence with Dumbarton Athletic where he would win two Scotland caps against Wales. His switch to Everton in 1889 brought his association with the Scotland team abruptly to an end.

[8] Bradford Daily Telegraph, November 18, 1885, 2

[9] Dumbarton Herald, October 03, 1888, 5

[10] Ibid

International Honours

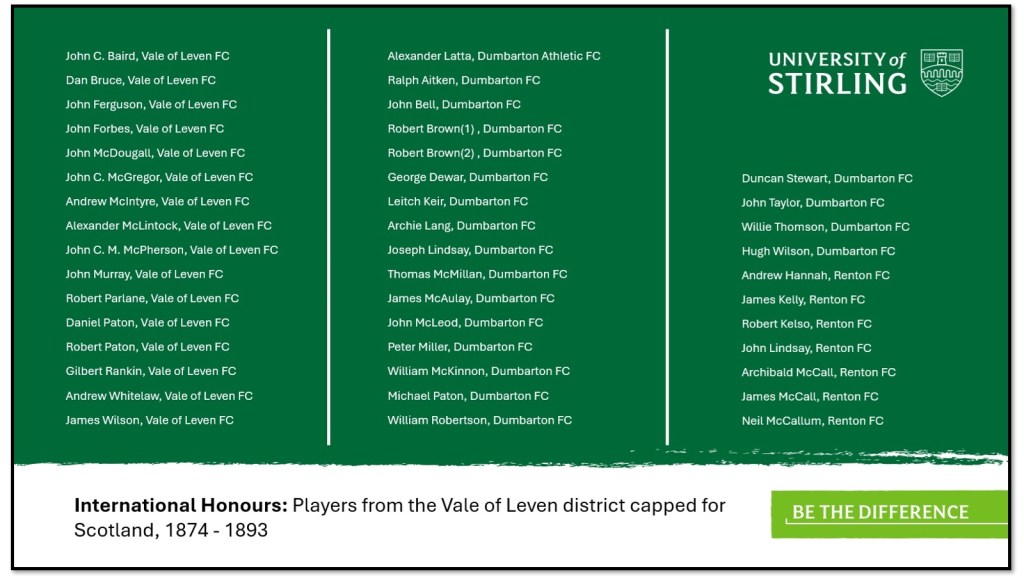

Players from Dunbartonshire were a regular feature of Scotland teams between 1874 and 1893. In total, 43 players from the Vale of Leven district were capped for Scotland during this time. One of the most notable contributions came in 1878 with Scotland’s 7-2 victory against England. Three players from Vale of Leven FC featured in this game and one of them, John McDougall, became the first Scot to score a hat-trick at international level. In the 1884 international against England five players from the Vale of Leven district were selected. Even with the significant loss of players to clubs across the border post 1885, the Vale of Leven teams continued to be an important supplier for Scotland.

Vale of Leven and the “Scotch Professor”

The Vale of Leven district appears to have made a decent contribution to the number of Anglo-Scots. Once professionalism was legalised in 1885 the number of players crossing the border rose significantly. For this study, a brief investigation into the number of Anglo-Scots from the Vale of Leven area unearthed a total of 66 players. This number will almost certainly increase further with a more detailed analysis.

End of an era

All three clubs were founding members of the Scottish Football League in 1890 but the advent of professionalism in Scotland, three years later would have an adverse effect as each club struggled to compete in a rapidly changing market. From being Scottish Cup finalists in 1895, Renton would be forced to resign from the Scottish Football League only four games into season 1897-98. The club largely struggled thereafter and folded altogether in 1922. Dumbarton, despite their early League success, struggled in the years leading on from professionalism. Having been wound up in 1901 the club was reconvened four years later and has largely remained in the lower divisions of the senior game. At the end of season 1891-92, Vale of Leven FC had to drop out of the Scottish Football League after failing to win a single game. They remained in the lower levels of the senior game until being wound up in 1929. The present junior club bearing the same name was established a decade later. The old Vale of Leven players from the great cup winning era continued to meet up until well into the 1920s. By 1933, Andrew McIntyre and John McPherson, by then the last surviving members, were in agreement that the silver chalice be presented to the Vale of Leven District Council. This duly happened in January 1934. The Loving Cup has been loaned to the Scottish Football Museum for display for the past 23 years and alongside documents and artefacts from the Renton FC collection, will help to recount the story of the footballers from the Vale for generations to come.